Investigating the 1987 Stock Market Crash

Andy Constan was a second-year analyst at Salomon Brothers when the stock market declined 23% on Black Monday. Selected to participate in the Brady Commission’s investigation of the market crash, he learned exactly why and how it occurred.

On 19 October 1987, “Black Monday,” the US stock market crashed, with the Dow Jones index falling 23% after it had already fallen 10% over the three previous trading days. I was 23 years old and had been working at Salomon Brothers for a year as a corporate finance analyst. The job was a two-year stint where at the end you left to go to business school. It was a thrilling job.

My specific role was as a quantitative analyst, or “quant,” explaining complicated securities to corporate and capital markets clients. In 1987, equity index options were only four years old, convertible bonds were exotic, and rights offerings were uncommon. I was a resource for bankers, traders, and salespeople to help them sell the products Salomon had dreamed up. I was a busy guy. I had a couple of really nerdy superiors and people were more comfortable asking me to talk to their clients.

My colleagues’ inclination to call on me might also have been because at the time I was extremely connected to the New York club scene. My analyst class, and many associates and VPs, came to the parties I hosted at Area, Limelight, The Tunnel, and other super-hot clubs of the day. Anyhow, I was well known.

After Black Monday, President Reagan asked Nicholas Brady, the CEO of Dillon Read, to put a task force together to study why the crash happened and suggest ways to prevent such a crash from happening again. Brady gave the chief of staff job to a guy who had just joined Salomon in banking named Chas Phillips. The staff was to be comprised of academics and Wall Street guys.

Goldman chose Michael Cohrs, who ran equity capital markets; Morgan Stanley picked Scott Lenowitz, who ran program trading; JP Morgan chose Peter Bernard, who ran fixed income derivatives; Lehman picked Phil Jones, who ran equity derivatives structured products; Tudor Investment chose Peter Borish, head of research; and Salomon chose … me, a second-year analyst! I have no clue why Salomon picked me. I was obviously so much more junior than any other appointee. Maybe it was because the chief of staff job had already gone to a senior Salomon guy or maybe they figured they needed a grunt to do the unglamorous work. I did end up making all the exhibits for the task force’s 396-page report, so maybe that was it.

We met at the Federal Reserve building on Maiden Lane. You might know it from Die Hard with a Vengeance. It’s where they keep the gold. We got a cool tour from Gerry Corrigan, the New York Fed governor.

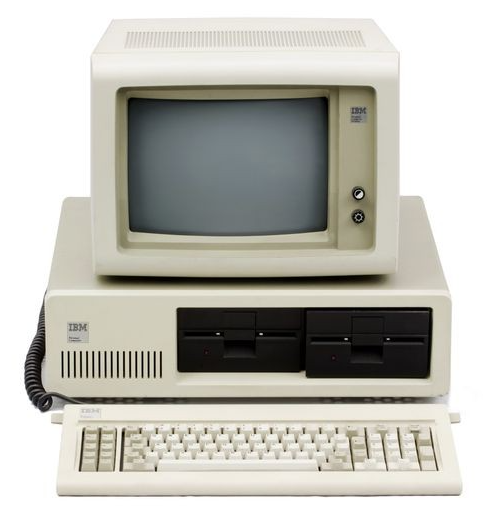

We started to comb the data. There was no Excel at the time and we only had an IBM AT with Lotus 123. Nonetheless, the data we had was fantastic. We had every equity index futures trade done by every executing broker tagged with the end client’s name. At the time, equity future orders were phoned in to the Chicago exchanges; the CME (Chicago Mercantile Exchange) for the S&P 500 and the CBOT (Chicago Board of Trade) for the Major Market Index.

Photo by Mark Richards for Computer History Museum. Used by permission.

The DOT system (Designated Order Turnaround), around since 1976, had been upgraded in 1984 to allow brokers to send orders of up to 100,000 shares directly to specialists on the New York Stock Exchange floor where trades were arranged. The system avoided the army of floor brokers who carried paper tickets to specialists for execution. DOT gave us trade-by-trade data, naming buyers and sellers, and indicating whether the trade was part of a larger program trade, that is, trades of a basket of stocks sold or bought all at once.

We could also figure out when program trades and equity index futures trades were done for index arbitrage. In index arbitrage, traders buy and sell equity indices in the futures market and baskets of individual stocks replicating equity indices in the cash market. They buy the cheaper and sell the more expensive and until their actions push futures and cash prices into alignment. In normal times, this arbitrage keeps cash and future prices within the difference of transaction costs.

As I mentioned, equity index options had only been invented in 1983, but the market had already identified the options’ “volatility skew.” The prices of out-of-money options implied a higher price volatility of the index than did at-the-money options. This suggested that an equity investor wanting to protect itself from a steep portfolio decline paid more for an out-the-money put than the investor theoretically should pay. A few “bright” guys got together and founded a firm that marketed a cheaper way to purchase downside protection. The firm was named LOR for Leland, O’Brien, and Rubinstein. You may recognize the last name as he and another academic named Cox wrote one of the bibles of option theory and invented the binomial tree approach to valuing options. These guys sold their service to the biggest pension funds in the world. The idea was that instead of buying expensive puts, the pension fund would follow LOR’s proprietary algorithm to dynamically replicate a put at lower cost. They gave it a catchy name: Portfolio Insurance.

Following the “algo” and dynamically replicating a put requires a strategy of selling equity index futures or a portion of one’s own portfolio when the market falls and buying the future or stock back when the market rises. It’s a sell low and buy high strategy. That seems stupid, but by doing so one cuts exposure as the market falls and adds back exposure as the market rises. The losses taken in this activity were supposed to be less than the price of a put. In option terms, if realized volatility is less than option-implied volatility, LOR’s option replication strategy is cheaper than buying options. The problem was that LOR and its imitators sold the idea to too many investors. The task force I was a part of discovered that when the October 1987 crash occurred, $60-$90 billion of equity assets were being dynamically hedged. These “portfolio insurers” underestimated the liquidity effect, the downward pressure on prices, of all of them selling into a falling market at the same time.

The Wednesday morning previous to Black Monday, US interest rates rose owing to a greater-than-expected trade deficit and the belief that the US dollar would have to fall before the deficit could narrow. This started equities down, as increased interest rates made bonds relatively more attractive than stocks. The same morning, legislation to eliminate tax benefits associated with leverage buyouts was introduced. This caused the stock prices of potential takeover candidates to fall. The Dow fell 44 points (1.8%) in half an hour.

The task force’s data told us who sold and bought what. I drove the keyboard of the IBM PC AT in Gerry Corrigan’s office as the senior guys looked over my shoulder and we constructed a timeline of market events. Portfolio insurers reacted to Wednesday morning’s stock price decline by selling index futures in an amount equivalent to $530 million of stock. The decline in the futures market from this selling was transmitted to the cash market by index arbitragers. As a result of portfolio insurers bringing index future prices down with their selling, and index arbitragers pushing the cash market down into alignment with futures, the Dow fell another 51 points and ended the day down 3.8%.

Over the three trading days leading up to Black Monday, portfolio insurers and index arbitragers were joined by two other types of market participants in pushing equity prices lower. Equity mutual funds, receiving redemption demands and expecting to receive more such demands, sold into the declining market to raise cash for those redemptions. Finally, opportunistic traders, who usually opened and closed out their positions within the same day, predicted that the decline in equity prices would cause portfolio insurers and equity mutual funds to continue selling. These “day traders” sold equities short, expecting to buy back their positions at lower prices. Their short selling also pressured prices to decline.

At Friday’s close, the Dow had fallen 262 points, or 10%, in three days. Portfolio insurers had sold $3.6 billion of equity index futures over the three days. But their portfolio hedging algorithms told them that they were at least $8 billion behind what they should have sold! Some equity mutual funds were also behind in selling stock to fund redemptions, as their redemptions had been $750 million greater than their stock sales. Day traders also helped pushed prices down. On Friday alone, the seven most active day traders sold short $1.4 billion and bought back $1.1 billion, suggesting a $300 million profit. This was the situation when the markets opened on 19 October 1987.

At the open Monday morning in Chicago, portfolio insurers sold equity index futures equal to $400 million of stock and the indices fell. When the New York Stock Exchange opened later, it was overwhelmed with sell orders. Even though many stocks did not open, first hour volume was $2 billion. Of this, $250 million was from index arbitragers selling in the cash market to take advantage of the fall in futures, $250 million was from portfolio insurers selling stock, and $500 million was from a single mutual fund selling to fund redemptions.

The index arbitragers were in for a rough morning, especially. They wanted to sell stock in the cash market and buy equity index futures because futures had become so much cheaper than cash. But during the first hour of stock market trading, the S&P and Dow cash indices reflected out-of-date Friday closing prices because many stocks had not opened. The arbitragers sent sell orders to the cash market. As more stocks opened, they opened at much lower prices than the index arbitragers expected. When the cash market fulfilled the index arbitragers sell orders, the arbitragers discovered that the futures market was really not so much cheaper than the cash market and the arbitrage was not there. The index arbitragers rushed into the futures market to buy, not to lock in profits, but to avoid greater losses. Their buying pushed futures higher and the cash market, maybe thinking that the bear market in futures was over, began rising at 10:50 am.

At Drexel Burnham, a trader stood up at his desk and started buying enthusiastically, expecting the markets to continue to climb. But within an hour, a new wave of portfolio insurer sales killed the rally and sent futures and cash stocks crashing down. Between 11:40 am and 2:00 pm, portfolio insurers sold the equivalent of $1.3 billion in the futures market and $2.0 billion in the cash market. The Dow fell 9% over those two hours and twenty minutes!

The rally had only lasted an hour and the Drexel trader got run over. That’s the problem in manic situations like Black Monday. You may think a price is ridiculous given accounting and economic fundamentals. The price might objectively be ridiculous. But if the price is already ridiculous per your valuation techniques, the price might become even more ridiculous. Traders speak of “trying to catch a falling knife.”

From 2:00 pm to 2:45 pm the cash market rallied 2.6%, but then a new wave of $660 million in futures selling drove that market down. Index arbitragers stayed on the sidelines, worried about execution in the cash market and a rumor that the cash exchanges might close early. Without index arbitragers keeping markets aligned, the futures and cash markets became disconnected, with the futures market finally falling 29% and the cash market falling 23% on the day.

Monday’s rout had been caused by only a few institutions making massive trades. Three portfolio insurers sold a total of $2 billion in the futures market, three portfolio insurers sold $2.8 billion in the cash market, and a few mutual funds sold $900 million in the cash market. We summed up the effect of all this selling and the cause of the crash in our report: overestimating market liquidity led certain investors to adopt strategies calling for more liquidity than the market could supply.

We saw it all in the trading data the Fed gathered for us and in our report we described trades without naming the specific portfolio insurers, index arbitragers, mutual funds, and day traders. To this day, I don’t think anyone knows their names unless they were told by one of the five of us who huddled over the IBM PC AT in Gerry Corrigan’s office in late 1987.

Our recommendations are still in place. Prior to our task force, the CME and NYSE didn’t have coordinated market closure procedures. We invented the stock market circuit breakers now in place. We also said that the plus tick rule failed to protect market function and it was eventually abandoned.

The experience was a blast for a 23-year-old kid who held what amounted to a temporary job at the lowest level of Wall Street hierarchy.

Andy didn’t go back to school after his two-year stint and instead remained at Salomon for 17 years, eventually rising to head of global equity derivative sales, trading, and structured products. After Salomon, Andy started two relative value hedge funds specializing in multi asset volatility arbitrage and capital structure arbitrage. Over the last 12 years, he has developed a strong expertise in macro investing, working at Bridgewater Associates as an Idea Generator and most recently at Brevan Howard as Chief Strategist. He is currently CEO/CIO of Damped Spring Advisors. In all, he has spent 35 years investing and trading global markets. His market commentary and stories can be found on Twitter at @dampedspring.

To comment on a story or offer a story of your own, email Doug.Lucas@Stories.Finance

Copyright © 2022 Andy Constan. All rights reserved. Used here with permission. Short excerpts may be republished if Stories.Finance is credited or linked.